This article by Shamus Milne originally appeared in the Guardian.

The Tory leader’s eagerness to brand not only miners’ leaders but the Labour party as enemies of democracy was a measure of her extremism and determination for class revenge

Thirty years ago, Margaret Thatcher branded striking miners “the enemy within”. The chilling catchphrase embodied her government’s scorched earth onslaught on Britain’s mining communities – and gave the green light for the entire state to treat the miners’ union as outlaws.

Now we know that the Tory prime minister intended to extend the charge of seditious insurrection, not only to leftwing Labour councils in Liverpool and London resisting cuts in services, but against the Labour party as a whole.

All were “enemies of democracy”, she planned to tell the Tory conference, the publication of her private papers now reveals. It was only as a result of the IRA bomb attack on her Brighton hotel that she was prevailed upon to drop the line as too divisive.

The fevered extremism of her comments – Labour’s leader Neil Kinnock was even absurdly described as a “puppet” of the miners’ president Arthur Scargill – are a reminder of the vengeful class fury of her government. Those who stood to defend union strength and the post-war social democratic settlement were seditious outsiders, to be destroyed in a domestic reprise of her Falklands campaign against the Argentinian dictator General Galtieri.

But the remarks also reflect her government’s systematic resort to anti-democratic measures to break the resistance of Britain’s most powerful union: from the use of the police and security services to infiltrate and undermine the miners’ union to the manipulation of the courts and media to discredit and tie the hands of its leaders.

A decade after the strike, I called the book I wrote about that secret war against the miners The Enemy Within, because the phrase turned out to have multiple layers of meaning. As the evidence has piled up with each new edition, the charge that Thatcher laid at the door of the National Union of Mineworkers can in fact be seen to fit her own government’s use of the secret state far better.

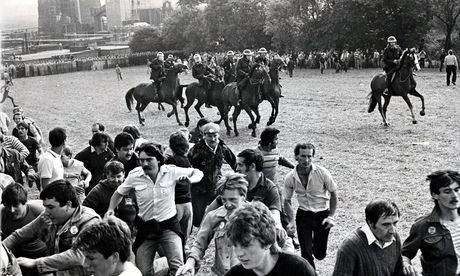

It wasn’t just the militarised police occupation of the coalfields; the 11,000 arrests, deaths, police assaults, mass jailings and sackings; the roadblocks, fitups and false prosecutions – most infamously at the Orgreave coking plant where an orgy of police violence in June 1984 was followed by a failed attempt to prosecute 95 miners for riot on the basis of false evidence.

It’s that under the prime minister’s guidance, MI5, police Special Branch, GCHQ and the NSA were mobilised not only to spy on the NUM on an industrial scale, but to employ agents provocateurs at the highest level of the union, dirty tricks, slush funds, false allegations, forgeries, phoney cash deposits and multiple secretly sponsored legal actions to break the defence of the mining communities.

In the years since, Thatcher and her former ministers and intelligence mandarins have defended such covert action by insisting the NUM leaders were “subversive” because they wanted to bring down the government. Which of course they did – but “legitimately”, as Scargill remarked recently, by bringing about a general election – as took place in the wake of the successful coal strike of 1974.

In reality, as 50 MPs declared when some of these revelations first surfaced, Thatcher’s government and its security apparatus were themselves guilty of the mass “subversion of democratic liberties”. And, as the large-scale malpractices of police undercover units have driven home in the past couple of years, their successors are still at it today.

A generation on, it is clear that the miners’ strike was more than a defence of jobs and communities. It was a challenge to the destructive market and corporate-driven reconstruction of the economy that gave us the crash of 2008. The outcome of the dispute brought us to where we are today: the deregulated, outsourced, zero-hours world of David Cameron’s Britain.

That reality, and its vindication of the miners’ stand, is well understood 30 years later, and reflected in the power of contemporary films such as Pride and the new documentary Still the Enemy Within.

Three decades on, it has become ever clearer that it wasn’t the miners or their leaders who were the enemy within. It was the secret state and those who wielded it against people defending their livelihoods across Britain.